이집트 기록과 출애굽Exodus: 사라진 노예 인구의 증거

아멘호테프Amenhotep 2세 통치 시기 고대 이집트 비문은 기원전 15세기 중반, 이집트 왕국이 대규모 추방과 강제 노동에 집중했음을 보여준다.

성경 연대기에 따르면, 출애굽Exodus은 기원전 1446년경, 아멘호테프 2세 통치 7년째에 일어났으며, 60만 명이 넘는 남녀노소가 이집트를 떠나면서 전례 없는 노동력 부족 사태가 발생했다(출애굽기 12:37-38; 민수기Numbers 1:46).

이집트 기록은 이스라엘 백성의 추방을 공식적으로 인정하지는 않지만, 외국인 노예 포획에 엄청난 노력을 기울였음을 보여준다.

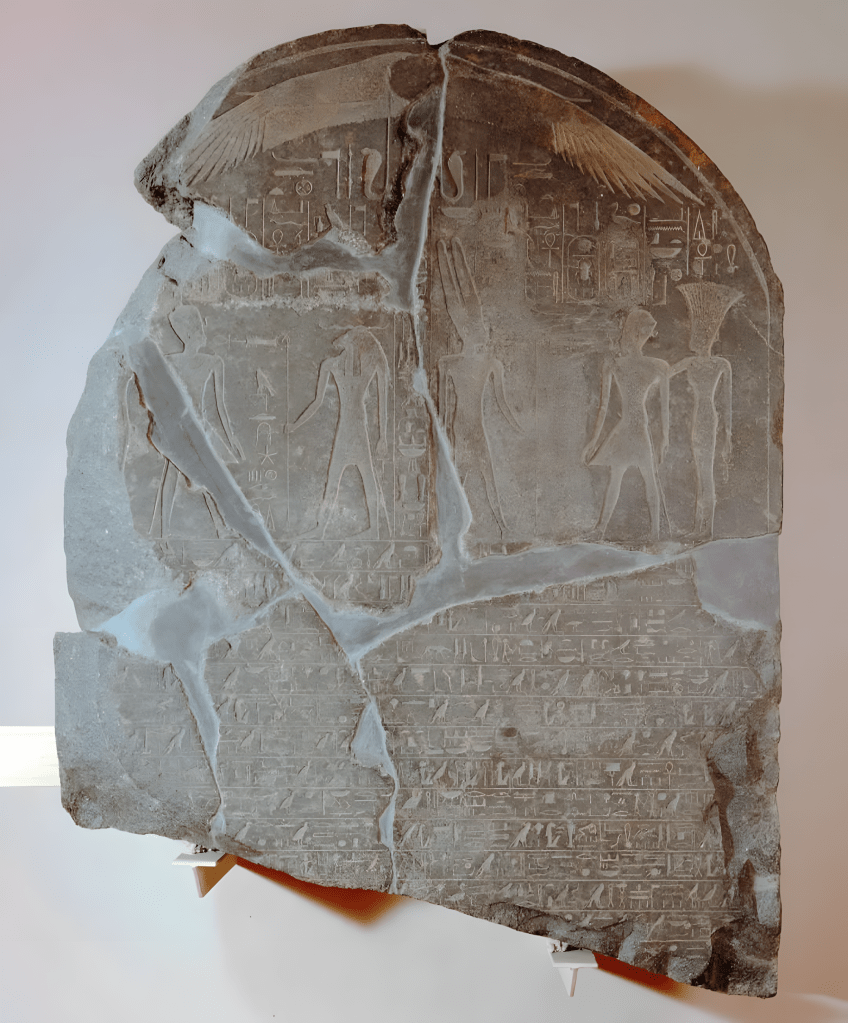

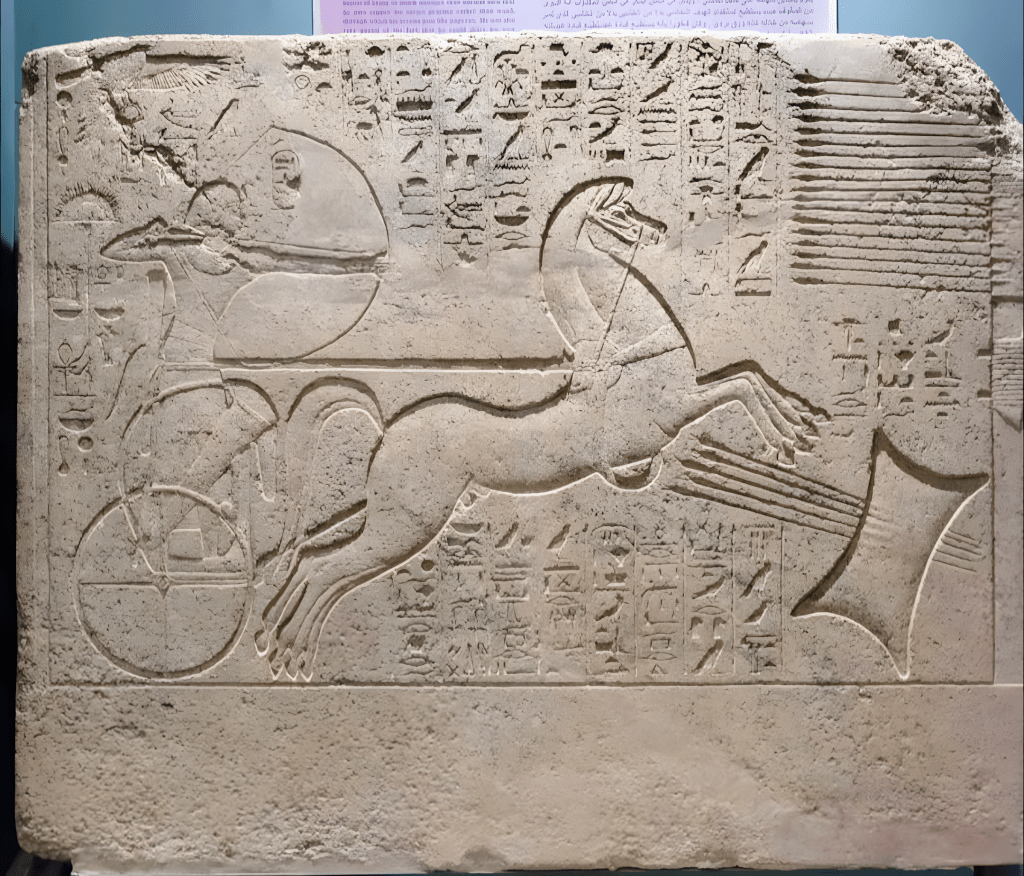

이는 세 가지 주요 유물에서 확인할 수 있는데, 아시아 원정에서 포로로 잡은 약 89,600명을 기록한 멤피스 비석Memphis Stele, 10만 명이 넘는 포로를 포획한 것을 기념하는 엘레판틴 비석Elephantine Stele, 그리고…카르나크Karnak 신전 부조와 원정 목록은 레트제누Retjenu에서 외국인을 포로로 잡았다는 사실을 반복적으로 강조한다.

이러한 비문들은 이집트의 노동력을 복원하기 위한 일관되고 대규모적인 노력을 보여주는데, 이는 대규모 노예 인구가 갑자기 떠난 후 예상할 수 있는 바로 그러한 대응이다.

아멘호텝 2세는 출애굽 당시 파라오 중 역사적으로 가장 타당한 인물로 꼽힌다.

그의 통치 기간은 출애굽 시기가 초기라는 점과 일치하며, 대규모 군사 작전은 그가 갑작스러운 노동난에 직면했음을 시사한다.

그의 아버지 투트모세Thutmose 3세는 40년 이상 통치하여 모세가 이집트에서 성장하고 미디안으로 피신했다가 성인 지도자로 돌아올 충분한 시간을 제공했다.

이는 장자의 죽음을 포함한 성경적 시간 순서와도 부합한다.

반면 람세스 2세는 이 두 가지 모두에서 부적합하다.

그의 통치 기간은 출애굽 시기보다 늦고, 아버지의 짧은 통치 기간은 모세가 미디안Midian에서 보낸 시간을 설명할 수 없다.

이집트 문헌에는 출애굽 기록이 없지만, 아멘호텝 2세의 대규모 군사 작전, 아버지의 긴 통치 기간, 그리고 사건 발생 시기를 종합해 볼 때 그가 모세와 마주한 파라오라는 주장을 강력하게 뒷받침한다.

종종 단순한 비유로 치부되는 성경적 이야기는 이집트의 정책과 군사 활동 구조 자체에 반영되어 있다.

Egyptian Records and the Exodus: Evidence of a Lost Slave Population

Ancient Egyptian inscriptions from the reign of Amenhotep II reveal a kingdom heavily focused on mass deportation and forced labor during the mid–15th century BC. According to biblical chronology, the Exodus occurred around 1446 BC, during Amenhotep II’s seventh year, when over 600,000 men, plus women and children, left Egypt, creating an unprecedented labor shortage (Exodus 12:37–38; Numbers 1:46).

Egyptian records, while never admitting the loss of the Israelites, reflect an extraordinary concentration on capturing foreign slaves. This is seen in three key artifacts: the Memphis Stele, which records roughly 89,600 prisoners taken in an Asiatic campaign; the Elephantine Stele, commemorating the seizure of over 100,000 captives; and the Karnak reliefs and campaign lists, which repeatedly emphasize the capture of foreigners from Retjenu. These inscriptions demonstrate a consistent, large-scale effort to restore Egypt’s workforce, exactly the type of response one would expect after the sudden departure of a massive slave population.

Amenhotep II emerges as the most historically plausible Pharaoh of the Exodus. His reign fits the early-date chronology, and the scale of his campaigns suggests he was dealing with a sudden labor crisis. His father, Thutmose III, ruled for over 40 years, providing ample time for Moses to grow up in Egypt, flee to Midian, and return as an adult leader—matching the biblical timeline, including the death of the firstborn. By contrast, Ramesses II fails on both counts: his reign is too late for the early Exodus, and his father’s shorter rule cannot accommodate Moses’ years in Midian.

While Egyptian texts never record the Exodus, the combination of Amenhotep II’s massive military campaigns, his father’s long reign, and the timing of the events strongly supports him as the Pharaoh confronted by Moses. The biblical narrative, often dismissed as purely allegorical, is here mirrored in the very structure of Egyptian policy and military activity.

Far from contradicting Scripture, these records indirectly corroborate the Exodus, showing the profound impact a sudden loss of enslaved labor had on Egyptian society. The historical and archaeological evidence aligns with the biblical account, leaving a compelling case that the Exodus was not only possible but recorded in the responses of Pharaoh Amenhotep II himself.

댓글 남기기